Carepoint vending machine

Designing to build trust between people experiencing houselessness and medical providers

Quick info

Timeline: October 2021 to December 2021

Located: The Human Centered Design and Engineering department at the University of Washington

My role: User researcher, content designer, and UX designer

Design Question

How do we foster trust between medical providers and people experiencing houselessness, especially related to the COVID-19 vaccine?

Overview

As part of a graduate course in user-centered design, I worked with a group to create a concept named Carepoint.

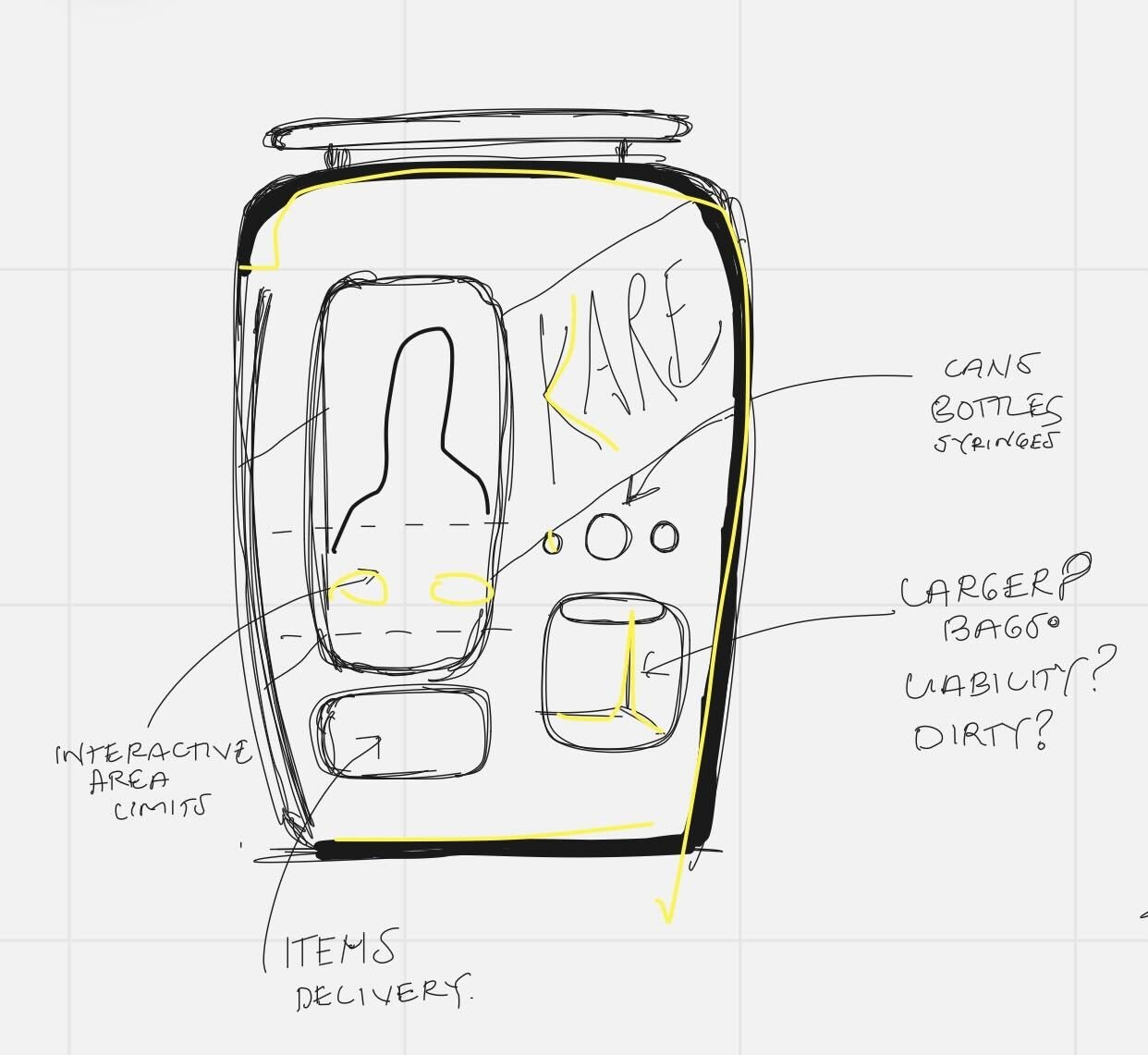

Carepoint is a vending machine built in a mobile privacy box that provides essential resources for people experiencing houselessness, including access to healthcare. Our solution is meant to be moved between encampments, shelters, and other public spaces.

Problem statement

As of December 2021, less than 65% of the US population is vaccinated against COVID-19. This number is estimated to be lower among People Experiencing Houselessness (PEH). While many factors contribute to vaccine hesitancy, one major problem is a general lack of trust between PEH and the U.S. healthcare system as a whole. We set out to develop a design solution to help build and maintain trust between a city's unhoused community and local healthcare providers.

Houselessness and Covid-19 vaccination are complex issues, or “wicked problems.” Mistrust is not an issue that will be solved by a single vending machine. However we learned that one-on-one conversations between PEH and medical providers are important in creating trust. Carepoint attempts to tackle these wicked problems by connecting PEH with medical providers and supplying resources to the PEH community. With community buy-in, organizational support, and continuous user testing, we believe that Carepoint could be a vital tool in helping PEH stay safe and healthy.

Objectives

Build trust with PEH by supplying their basic needs while respecting their autonomy.

Allow healthcare providers to have more direct access to the PEH community.

Create a mutually beneficial environment between PEH and the local community.

Our Journey

Research

We encountered challenges on the pathway to our final proposal. Initially, our team’s scope was broad: we wanted to create a tool to battle misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine and address vaccine hesitancy. We explored different user groups through discussions about how to narrow the scope.

One group member suggested we explore vaccine hesitancy among the unhoused population. To better understand this problem, we used a range of different methods, including:

User interviews with healthcare workers, social workers and case managers, people experiencing houselessness (PEH), and other potential stakeholders

Secondary research that focused on relationships and interactions between PEH and healthcare workers

A 13-question survey to measure people’s experience and opinion on vaccine hesitancy in the unhoused population (aimed at medical providers and other individuals who worked with PEH)

I co-led the user interview and survey portions of the user research.

What we learned

We learned that PEH don’t necessarily mistrust the COVID-19 Vaccine, but they mistrust the healthcare system overall.

Survey respondents reported that vaccine hesitancy is common in the unhoused population. Our most critical research finding confirmed a general mistrust in the healthcare system by PEH.

The healthcare workers, social workers, and case managers mentioned that PEHs have a lack of trust toward medical providers. This was a critical finding because our interviews with the unhoused population did not reveal this mistrust. The PEH we interviewed expressed trust in the COVID-19 vaccine, which could indicate that the PEH generally distrust the medical system as a whole, not particularly the COVID-19 vaccine. Healthcare providers mentioned that there has to be a warm and respectful relationship between healthcare providers and PEHs in order to see successful vaccination outcomes.

Many PEHs had bad past experiences with healthcare providers. According to our secondary research, women experiencing houselessness described a loss of dignity in encounters with healthcare services. They also expressed that healthcare services could also offer respite, rest, and sanctuary at a time when they needed them most.

Additionally, the intersectionality between houselessness and groups who were historically mistreated by the healthcare system, such as people of color, contributes to distrust.

Several of our research methods revealed that one-on-one conversations are an effective method to encourage vaccination. Creating a human connection between a healthcare provider and PEH is crucial.

Based on our initial research, we came up with these personas:

These personas helped us identify our users’ needs and narrow the scope of our user base. We used these personas to inform our future design decisions.

Pivoting:

At this point in our journey, we decided to focus on building trust and create an artifact that benefited PEH people, healthcare professionals, and local communities. COVID-19 remains a component in our design, but is no longer the primary focus.

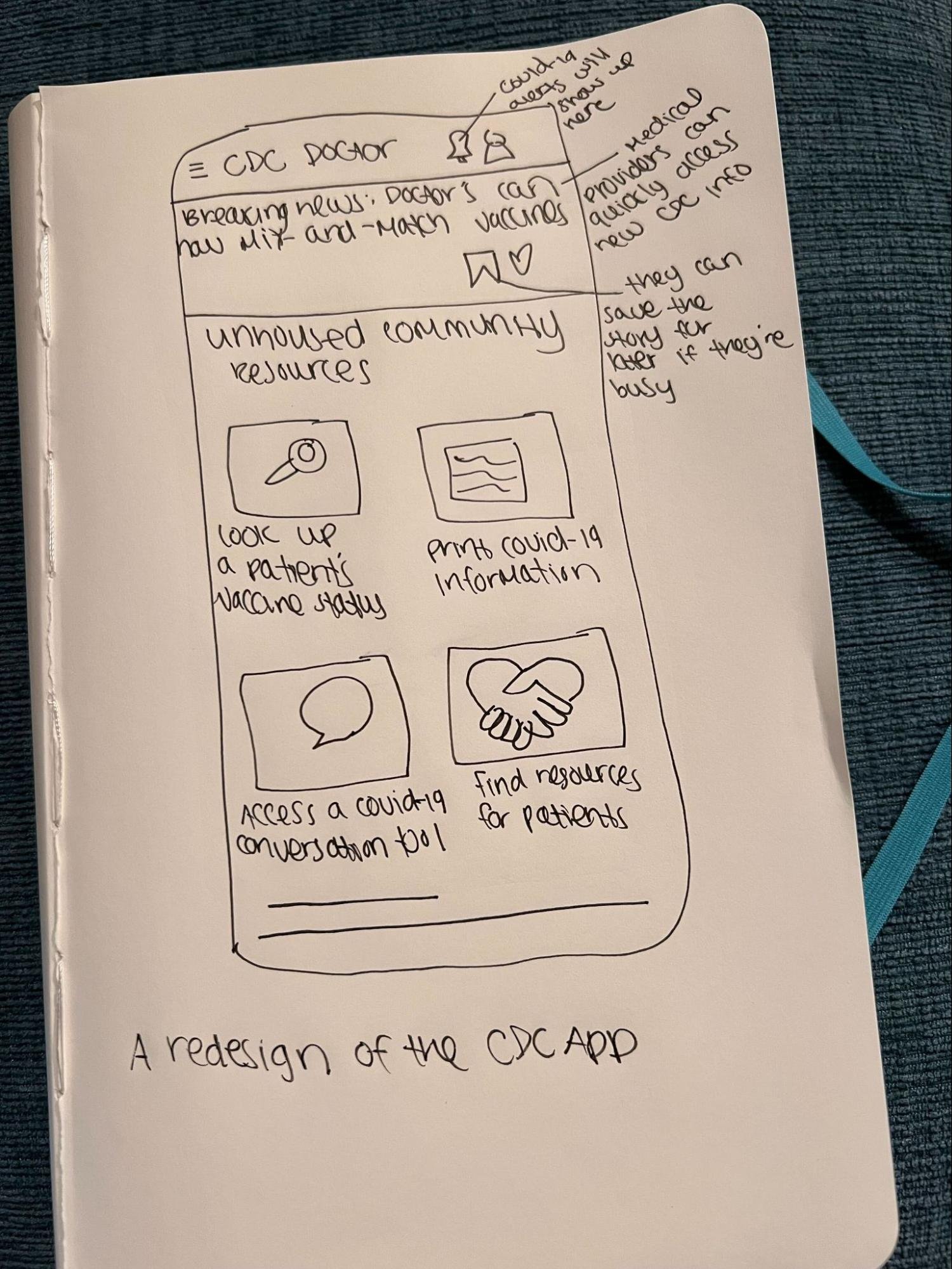

From our sketching brainstorming sessions, we arrived at three initial designs:

A redesign of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) app for doctors

A shared mobile doctors' office

A digital misinformation navigation system

The sketching exercise helped us break out of our comfort zone and examine the problem and potential solutions in new ways.

Finally, we combined elements of the three final ideas into one, which is how we arrived at Carepoint, a transportable vending machine.

Based on our initial rough prototype, we developed an information architecture diagram to map the user flows. I developed user flows to explore different user interactions. I included different accessibility experiences and included one back-end interaction (a healthcare provider answering a call from Carepoint). This helped us determine what functionality should be included in the design.

At this point in the design process, we were ready to build our first medium-fidelity prototype. In this prototype, we focused on the screen and not the physical aspect of the prototype. We aimed to gain feedback before we invested more time into creating a polished and comprehensive version of the machine. We also wanted to validate how we interpreted our user research and user needs in our design.

User Testing

We conducted moderated remote usability testing of our initial prototype. We tested the prototype in a group with four evaluators over Zoom. I narrated and administered the testing. Evaluators are estimated to be between 20 to 35 years of age. All are students at the Human-Centered Design and Engineering Program (HCDE). While testing our Figma prototype, one person shared the screen while other evaluators watched and offered feedback.

We updated several elements of the design, including making the layout of the language screen easier to use and including page transitions to allow users more flexibility in where they navigated next.

I worked with another team member to create the user interface for the high-fidelity prototype in Figma. In this design, we focused on user privacy, accessibility and inclusion, navigation, and the learning aspects of the UI. We followed industry best practices and insights from our user research. Additionally, we created a rendering for the physical pod. We wanted the physical pod to be transportable and accessible to people with disabilities, including wheelchair users.

The Carepoint vending machine has these four functions:

Connect PEH to healthcare providers

Provide basic and up-to-date information related to relevant public health information

Connect PEH to an existing resource

Provide essential hygiene/items to PEH in exchange for empty bottles or cans

Challenges:

Time and resources: Our team aimed to create a complex design artifact in only 9 weeks. We had to learn quickly and complete portions of the project with limited resources.

Scope: Our team started with a broad large and complex topic: to create a design solution that tackled raising the rate of Covid-19 vaccination. Even when we narrowed down to a specific user group (PEH in King County), the problem felt large and ill-defined. Our research helped us target a real issue (lack of trust), but throughout the project, we still struggled to keep our design artifact focused.

Ethics: Because our design’s target user group is a vulnerable population, we were very wary of taking advantage of unhoused people for testing and research. We approached each conversation with sensitivity, which definitely led to some barriers in our research. If we had more time, we’d want to design an ethical research plan with people who interact closely with members of the unhoused community.